By Shawn Hattingh

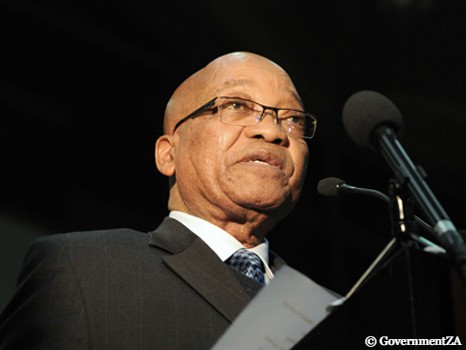

Various columnists and opposition politicians, whether from the Democratic Alliance (DA) or the Economic Freedom Fighters (EFF), have repeatedly called for Zuma’s head. They want him out and it is often insinuated that if he was gone things would be so much better. The latest round in this saga has been the recent vote of no confidence that was tabled by the opposition in Parliament.

Certainly, Zuma’s Presidency has been defined by nonstop scandal. There have been clear instances of him using his position for personal gain. News headlines have also repeatedly highlighted how members of his family, along with his allies, have benefitted from state tenders, or have been drawn into partnerships with certain capitalists, such as the Guptas.

Beyond this there have been outrages such as Marikana; the militarisation of the police; and the police being deployed in Parliament. Zuma too has even been accused of intervening via his Minsters and appointees to remove people in institutions such as the Hawks and the South African Revenue Services (SARS) that have allegedly threatened to investigate the financial scandals surrounding him and his allies.

In other words patronage and growing repression have been features of Zuma’s tenure.

Is it just Zuma?

The danger though of focusing solely on Zuma, and seeing all of the scandals as simply being linked to his clearly flawed personality, is that it runs the risk of missing the point that the happenings surrounding him are symptoms of much wider problems that exist in society. These problems are linked to how 1994 only brought liberation for a few; how white capital remained in control of the private sector; the form neoliberalism took in the country; how the state has been a key site for accumulating wealth; and how competition to gain top positions or access to the state has become intense. Linked to this, the turn towards repression under the Zuma administration is related to how there is a growing unhappiness amongst the black working class with all of this.

Liberation for a few

One of the problems that the events around Zuma are symptoms of is the elite transition that took place in South Africa. Indeed, 1994 did not bring liberation for the working class, and the black section in particular.

Rather it was a deal between a black and white elite. As part of this deal, white capitalists were assured that their wealth would not be touched; in return the ANC leadership was allowed to take over the state. In other words, capitalism was maintained, including the harsh exploitation of the black working class, but the faces in the state changed.

In this context, and in the context where apartheid stunted the rise of black capitalists, the state or links to it have become the key site through which an ANC elite could build itself into a prosperous black section of the ruling class.

The state and accumulating wealth

This was possible because the state as a structure not only protects and furthers the interests of sections of capital under capitalism, and ensures minority class rule, but it also generates a section of the ruling class in the form of the top politicians and top officials that head it. Those that join the state enter into positions of power and privilege: they can and do rule over others and they can and do use their positions in the state to accumulate wealth. In fact, there is a long history across the world of a state-based elite, including former liberation heroes, using their positions for self-enrichment – this to a greater or lesser degree has been and is a feature of all states.

Sections of the ANC elite have, therefore, been using the state since 1994 to accumulate wealth through various ways including large salaries and perks for top positions in the Executive, Parliament, government departments and parastatals. At times self-enrichment has also taken the form of corruption. Likewise, links to the state or top politicians have also ensured access to Black Economic Empowerment (BEE), tenders from the state associated with neo-liberalism, key deals related to public-private partnerships, and directorships in established private corporations. This has been vital in building up the wealth of sections of the ANC leadership since 1994. Like Zuma, both Mandela and Mbeki – and those close to them – became rich through the state. The tendency to use the state for self-enrichment, therefore, did not just begin with Zuma and it won’t end with him either.

Of course, the ANC also had its predecessors. In all of this too there are echoes of how an almost exclusively white-based ruling class, along with a ‘homeland’ elite, used the state to leverage opportunities for self-enrichment under apartheid.

Head the state at all costs

The fact that the state has been key to accumulating wealth for sections of an ANC aligned elite has meant that competition for access to top state positions has been intense. Many factions in the ANC have wanted and continue to want to enter into the state or have access to its resources.

Many of those who backed Zuma against Mbeki were individuals – including Malema – that wanted access to top state positions, power or access to tenders. Some had been excluded in the past by the Mbeki faction, and they backed Zuma in order to gain access to the top of the state and the wealth that would bring.

Once they had thrust their man into the Presidency, the remnants of this faction – some have been excluded again like Malema – began brazenly using their connection to Zuma to accumulate wealth. Some received positions in the Executive and parastatals, others received tenders, many also used their connection to the Presidency to leverage business opportunities. It is also not an accident that under Zuma the number of Ministers and Deputy-Ministers has mushroomed.

With regards to Zuma himself, the benefits of heading up the state have been obvious. By one estimate if Zuma’s salary and perks – such as security, vehicles, and expenses for his wives – for the first term of his Presidency are added together, the cost would come to over R500 million.

Protecting at all costs

Using the state to accumulate wealth, however, also means that those who do so try and protect themselves and their allies from any consequences. This is the case especially if it is being done brazenly.

Zuma’s Minsters and appointees intervention in institutions such as SARS and the Hawks, and the firing of officials that have allegedly threatened to investigate Zuma and his allies has been, in all likelihood, about protecting Zuma along with others in the faction that promoted him.

In reality, a tendency towards protecting allies already existed during the Mandela and Mbeki administrations. In the early 2000s Mbeki, for instance, ensured that investigations into the arms deal were stalled. Mandela too protected Ministers that were involved in scandals such as Sarafina. Mandela at times used his power to push through unpopular policies such as the Growth Employment and Redistribution Policy (GEAR). Such actions, in all likelihood, emboldened and set a precedent that enabled Zuma to apparently so freely intervene in institutions such as SARS.

The reality though is that the use of power by those that head the state to try and silence potential whistleblowers or detractors is by no means limited to South Africa. Take the United States (US) as an example. During the terms of Bush and Cheney they openly lied in order to start a war in Iraq that proved very profitable for companies they were close to and they granted permission to the National Security Agency (NSA) to unlawfully wiretap citizens, including critics. Yet because they headed the state they were never brought to account – not unlike Zuma.

A turn to greater repression

The Zuma regime, however, has by no means had everything its own way. The brazen self-enrichment of the faction that elevated Zuma into power, and continued racial and class inequality in South Africa, has also meant that the ANC is beginning to lose its legitimacy amongst the black working class. Many within the working class, and black section of the working class in particular, can see how white capitalists continue to hold onto their ill-gotten gains and how a black section of the ruling class has joined them in a massive drive of self-enrichment. With massive unemployment, low wages, and mass poverty, large sections of the working class are getting very angry with this.

This has seen growing protests. In the past, the legitimacy that the ANC enjoyed meant a lid could be kept on this. This is no longer the case. In the face of growing protests, and in the face of losing legitimacy, the Zuma-led state – like states that have faced a similar situation – has turned towards repression. Hence the scandals such as Marikana and the militarisation of the police.

Conclusion

The scandals surrounding the Zuma regime, therefore, are symptoms of much deeper problems in South African society. Opposition parties can continue to believe that simply removing him will be a solution to almost everything. The reality is it won’t, there are massive problems at the heart of South African society and just getting rid of Zuma alone won’t change this. Ultimately only a struggle by the working class to fundamentally address the massive problems centred around inequality that the institutions and systems that uphold it, can end the symptoms we are seeing associated with the Zuma regime.