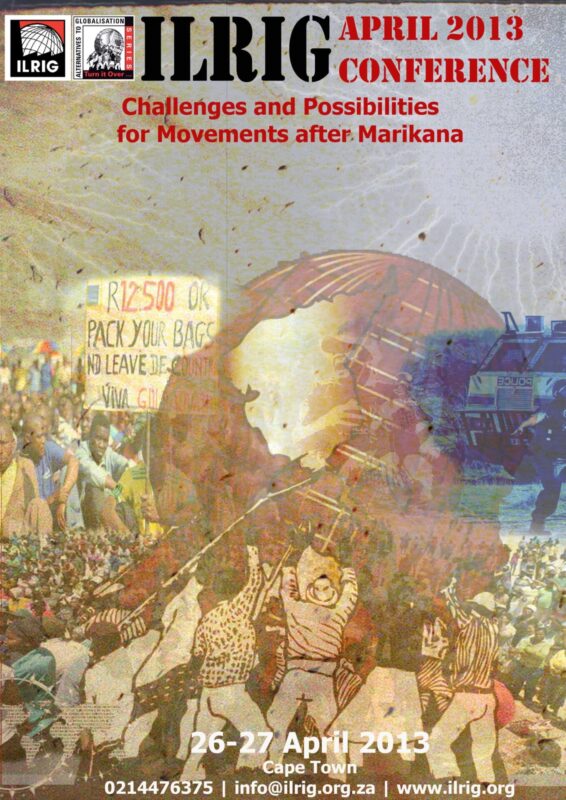

The 2013 ILRIG April Conference

New Forms of Organising: Challenges and possibilities for movements after Marikana

Community House, Salt River, Cape Town

26-27 April 2013

The April Conference is an annual gathering of about 100 activists. It is a space for activists and analysts to debate contemporary challenges facing the trade unions and social movements in South Africa and elsewhere.

In April 2013, ILRIG will be hosting a special conference of the new strike committees and other self-organised initiatives which have emerged after 2012’s Marikana massacre, together with activists who have been involved in the ongoing community protests of the last 10 years.

Since Marikana there has been a strike wave – which hasn’t entirely abated – of some 100 000 workers across the country – from the platinum province, to the coal and gold mines of the North West, Gauteng and the Free State, and from the workers at Kumba in the Northern Cape to Toyota in KZN, and even home-based textiles workers in Cape Town….and then in late 2012 farm workers in De Doorns.

A common feature of these strikes was that they were led and driven by self-organised workers’ committees – in defiance of the existing unions and of signed collective agreements made with these unions. This exercise in self-organisation was to impact on existing procedural wage negotiations – notably the transport sector, where employers and unions were about to reach an agreed wage settlement only to find that membership on the ground rejecting the proposed agreement and forcing through a protected strike. These strikes have joined the wave of community protests that have continued all over South Africa since the early 2000s. Something is stirring from below…the seeds of a new movement are possibly being planted.

Neoliberalism has not only been about privatisation and global speculation. It has also been about restructuring work and home. Today casualisation, outsourcing, work from home, labour brokers and other forms of informalisation have become the dominant form of work, and shack-dwelling the mode of existence of the working class. The latter is in direct proportion to the withdrawal of the state from providing housing and associated services. By way of contrast, the dominant trade unions in SA have largely moved upscale – towards white collar workers and away from this majority. Today the large COSATU affiliates are public sector white collar workers – like the SA Democratic Teachers’ Union (SADTU). The lower level blue collar workers are now in labour brokers and in services that have been outsourced – like cleaning, security etc – so they do not fall within the bargaining units of the Public Sector Bargaining Council.

While what is today the working class is largely a mass of working poor, informalised and casualised and eking out lives in urban and rural shanty towns, COSATU has been moving upstream. Many analysts have already been spelling out the changing nature and composition of COSATU affiliates’ members – the preponderance of white collar public sector workers; the beneficiaries of affirmative action in the public sector and so on. They have also looked at the changing nature of the composition of COSATU’s biggest affiliate NUM. That, as the mining industry was casualised and dominated by outsourcing, NUM’s membership base shifted to the skilled technicians and the white collar above-ground staff with little contact with the rock face workers.

And how did the institutions of South Africa’s industrial relations perform? Well, from the viewpoint of peace and productivity they certainly did their job. Strikes have shown a steady decline since 1995 – with only 2010, the year of public sector strikes as unions and state departments found themselves at the end of a 3-year agreement in that year, showing an increase in the number of strikes and days lost. The CCMA, in the meantime has increased its case handling exponentially, and has become an established part of the industrial relations landscape.

But from the side of ordinary working class people the system has been a disaster on every score. Overall workers’ wages and salaries as a percentage of national income have been dropping every year and were overtaken in 1999 by profits. In other words there has been a massive transfer of wealth from the poor to the rich in the era of the current industrial relations system.

Internationally, the trade union movement has often gone through periods of stagnation and co-option only to be revived by internal rebellions against the established industrial order. Trade unions originated in Britain as “trades unions” – where the older term, “trades”, referred to the skilled trades of craftsman. The movement arose from 2 sources – one conservative and protective of the old guilds and craftsman resisting the hordes of newly-proletarianised, deskilled workers; the other a militant offshoot of the 19th century radical Chartist movement. The first shop stewards were factory (or “shop”)-based representatives who led a radical democratic movement against the craft unions in the late 19th century and established the modern labour movement. Similarly in the USA, the older craft-based American Federation of Labour (AFL) experienced a revolt by industrial workers in the 1920s against the sweetheart nature of the AFL and its protection of skilled white workers. These militant industrial workers – newer immigrants and many black – grouped under the Congress of Industrial Organisations – fought the labour elite and forced it into an amalgam, the AFL-CIO, which is still the USA’s trade union centre today.

So worker rebellions against “their own unions”, against the “legal framework” for collective bargaining, have a distinguished history.

The appellation, wildcat, may invoke images of an unruly mob. And the demand for R12 500 may appear unreasonable and outrageous to commentators who can’t credit workers with any power to think for themselves. But what has been the most striking feature of the strike wave – particularly in the mining sector – has been the level of sophistication displayed, with no full-time organisers, no back up offices and no administrators; and against all the whole gamut of the state and civil society – from the mine owners media, to the political parties and the trade unions themselves.

As ever, there are no guarantees and the best efforts of the striking workers may be defeated by the sheer range of forces lined up against them. But for now the Strike Committees across the mining industry have formed their own structure – the National Strike Committee – and within this there is lively debate about where this initiative will go and what its strategic orientation will be – whether to continue as the Strike Committee and become a new form of collective bargaining, transform into a broad Labour Front or oversee mass enlistment in one of the existing unions.

Key challenges for the newer movements include:

– Are these instances of self-organisation mere pre-cursors to the inevitable emergence of industrial trade unions, as they are known today, or are they new forms of collective bargaining which will call into question all the traditions, institutions, policies and legislative frameworks of the current system of labour relations?

– How do workers achieve forms of collective bargaining given the extraordinary nature of these new forms and what are their strategic and tactical challenges if they are to revitalise the labour movement?

– Are the new forms capable of forging common struggles with the on-going community revolts and thereby become a broader force for social justice?

The conference will be over two and a half days (to allow for national and local travel) and will consist of three components:

– Inputs by representative voices from the various worker committees and other activist forums.

– Presentations by speakers on the basis of draft papers submitted by invited guests on the subject of new forms of organising here in South Africa and internationally.

– Workshopped and parallel sessions in which ILRIG facilitators engage the issues raised as facilitated sessions using educational methodologies