By Peter Cole

First published in Global Labour Column.

Benjamin Harrison Fletcher ranks among the greatest African Americans of his generation and the top echelon of Black unionists and radicals in all of US history. In his time, the early 20th century, Fletcher helped lead a groundbreaking union that quite possibly was the most diverse and integrated organization – not simply union – in an era rampant with racism, anti-unionism, and xenophobia.

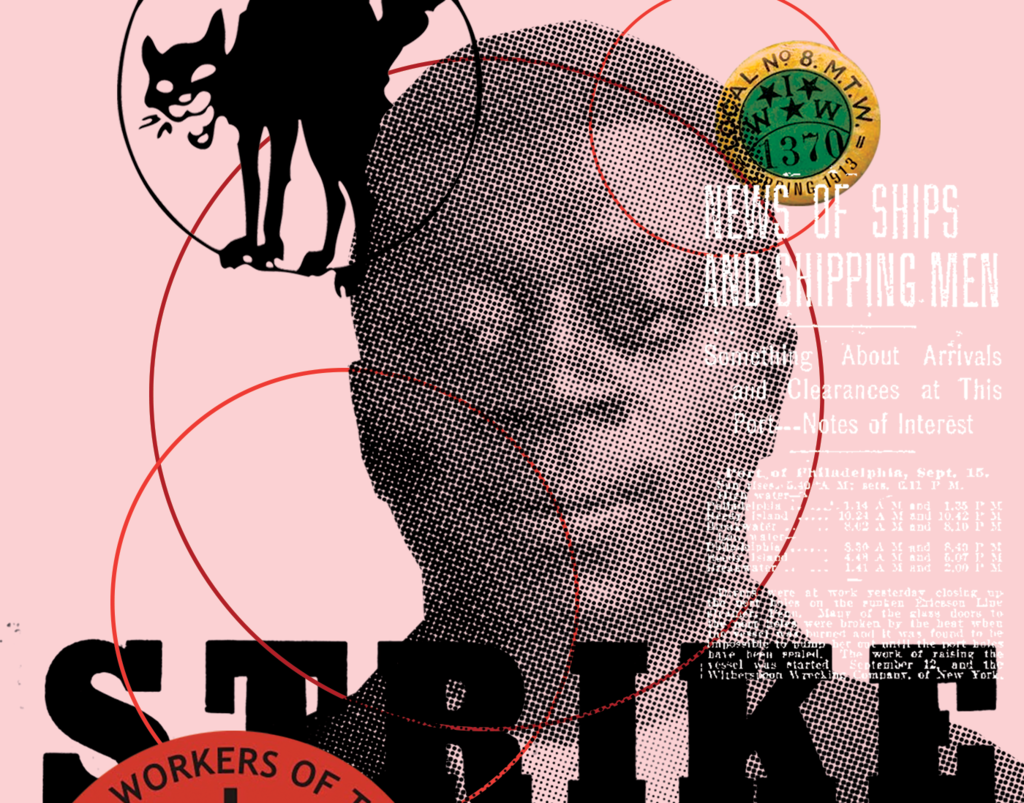

Fletcher and thousands of his fellow Philadelphia dockworkers belonged to Local 8, whose membership was roughly one-third African American, one-third Irish and Irish American, and one third European immigrant (particularly Italians, Poles and East European Jews). Chartered in 1913, amidst a successful two-week strike that shut down one of the country’s five busiest ports, Local 8 belonged to the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW). Perhaps the most radical union in all of US history, IWW members were affectionately known as Wobblies. Never before had there been a labour union like the IWW, whose founders included Eugene Debs, Mary Harris ‘Mother’ Jones, Lucy Parsons, and ‘Big’ Bill Haywood, who chaired the opening convention and called it ‘the Continental Congress of the Working Class’. While the IWW still exists, it was largest and most influential in the first quarter of the 20th century.

‘The workshop of the world’

If one has heard of A. Philip Randolph, Hubert Harrison, and Harry Haywood – Black working-class unionists and revolutionaries who lived in the US during the same era – then one also should know about Fletcher. If one has heard of militant Black American organizers of the 1960s such as Fred Hampton, Ella Baker, or Stokely Carmichael, one should know about Fletcher. Yet today, the greatest Black Wobbly is unknown save for aficionados of African American labour and radical history.

Fletcher was born in 1890 in Philadelphia. His parents had escaped the racist horrors of the South in the late 1880s, not long after the overturning of Reconstruction in what should be understood as a counter-revolution to preserve white supremacy, which came to be nicknamed ‘Jim Crow’. Although not definite, Fletcher’s parents were likely born enslaved in Virginia. In a sense, one might compare the migration of Fletcher’s parents to Philadelphia as similar to the many Sicilian immigrants escaping desperate poverty, or to Jews fleeing the murderous, anti-Semitic pogroms in Russia. In the working-class slums of south Philadelphia, African Americans such as the Fletchers lived on the same streets as East European Jews and Italians, as well as poor and working-class Poles and Lithuanians, Irish and Irish Americans, and others. Although long nicknamed ‘the City of Brotherly Love,’ Philadelphia was anything but, especially for African Americans. Multiple ‘race riots’ had occurred in the 19th and early 20th centuries.

Fletcher was one of the many thousands of young men who walked to the Philadelphia waterfront looking for work to support themselves and their families, as in port cities across the world. These sons of peasants—no daughters, then, loaded and unloaded ship cargo—submitted themselves to a hiring regime nicknamed the ‘shape-up,’ an exploitative system that drove down wages and divided workers.

In the early 1900s, Philadelphia boasted of being ‘the workshop of the world’, its factories manufacturing everything from buttonhooks and Stetson hats to locomotive engines and complex machinery. Alongside Chicago and other industrial cities, Philadelphia had made the United States into the world’s mightiest industrial powerhouse. This industrial powerhouse meant that there were many jobs unloading vast amounts of coal, iron, cotton, and other raw materials as well as loading all sorts of manufactured goods. Jobs, it must be noted, that were ‘casual’, back-breaking, incredibly dangerous, and very low-paying.

Local 8

Fletcher, who always went by ‘Ben’, started working along the shore and joined the IWW in 1910 or 1911, when he was about 20 years old. He quickly developed into an accomplished street speaker—nicknamed a soapboxer for the wooden boxes that speakers stood atop to be seen and heard above the crowds that jostled together on the bustling streets of ‘South Philly’. It is also worth noting that most of the people who he organized and addressed were European immigrants and European Americans. In 1913, at the age of 23, he became a leader in the newly created Local 8, born out of a victorious strike that had shut down one of the country’s busiest ports. He was regularly dispatched to other Atlantic coast ports such as Baltimore, Norfolk, Boston, and Providence to organize workers.

Local 8 went on to represent most dockworkers in Philadelphia for nearly a decade. It proved to be the IWW’s most successful at organizing a multiracial, multiethnic workforce, but it also was among the most durable branches—basically controlling waterfront labour for a decade. Local 8 also integrated work gangs (what I call ‘integration from below’) and social events as well as mandating equal racial representation among elected leadership.

Only a union such as the IWW could have organized such a diverse workforce, remembering that the working-class always has been more diverse than the middle or upper classes. In fact, the IWW had been founded in no small part because mainstream US labour unions, generally affiliated with the American Federation of Labor (AFL), refused to organize most Black, female, immigrant, or ‘unskilled’ workers. In other words, the AFL chose to ignore the great majority of the US working-class. Similarly, the International Longshoremen’s Association (ILA), segregated Black longshoremen in ‘Jim Crow’ locals.

Convicted for radical beliefs

Local 8 held on to power despite massive government repression as soon as the country entered World War I. In fact, Fletcher was the only African American among the 101 Wobblies convicted for violating the Espionage and Sedition Acts, for which he served two-and-a-half years in Leavenworth Federal Penitentiary. Notably, not a shred of evidence was introduced in his trial which proved Fletcher was guilty of any crime. Instead, he and all the other Wobblies were convicted for their radical beliefs which were deemed a threat, particularly during wartime. Despite losing its greatest leaders (not only Fletcher but five other Philadelphians also were imprisoned), Local 8 held on until late 1922 before employers retook control of the waterfront.

In his time, Fletcher was celebrated by the most prominent, radical Black intellectuals. A. Philip Randolph and Chandler Owen, co-editors of The Messenger, an openly socialist monthly published in New York City’s Harlem neighborhood which billed itself as the ‘only radical Negro magazine in America’, regularly praised Fletcher and Local 8. In 1923, they labeled Fletcher ‘the most prominent Negro Labour Leader in America’. Claude McKay, a Jamaican-born writer, Harlem Renaissance celebrity, and committed anti-capitalist, told of the story of Local 8, and thus Fletcher, in the legendary novel Home to Harlem (1928). W.E.B. Du Bois, a co-founder of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People and editor of its influential monthly, wrote: ‘We respect [the IWW] as one of the social and political movements in modern times that draws no color line.’ Of course, it was Local 8, led by Fletcher, that turned the Wobblies’ antiracist vision into that reality.

Sadly, Ben Fletcher was typical of non-elites in that he did not leave nearly enough of a paper trail behind. He did not have children to pass along his stories and memories to, and all of his friends passed away long ago. He was even buried in an unmarked grave. More than seventy years after his death and an entire century since he ‘made’ history, a complete biography of Fletcher seems impossible. Fortunately, he was important and respected enough that some of his writings have been preserved and numerous others documented his exploits. Ironically, another useful source of information comes from the federal government’s spies and prison wardens who documented Fletcher’s activities.

Ben Fletcher: The Life and Times of a Black Wobbly gives Fletcher some of the attention he deserves at a time when there is ever more interest in organizing African Americans and other workers of colour in the US. Due to the police killing of George Floyd, Breonna Taylor, and others, there has been more attention on white supremacy and support for racial equality than in decades. My book positions Fletcher at the center of (dock) worker organizing in the early 20th century. He constantly reckoned with the thorny dynamics of race and class along with the benefits and limitations of direct action tactics that the Wobblies were famous for. Ben Fletcher’s story complicates US labour history along with histories of American radicalism and Black studies.

Fletcher appreciated and embodied the notion that only worker power, at the point of production, could usher in a new society, worldwide. He knew, from personal and union experiences, that doing so demanded, first, obliterating the colour line. Local 8 built the sort of durable, diverse union which necessarily supported workers’ immediate needs while also advocating for working-class solidarity and socialism. As a consequence, Fletcher was deemed too radical by some and too conservative by others. Fletcher was, to quote John Lennon, a working-class hero who led an interracial, predominantly Black labour union. His story is as relevant in 2021 as it was a century ago.