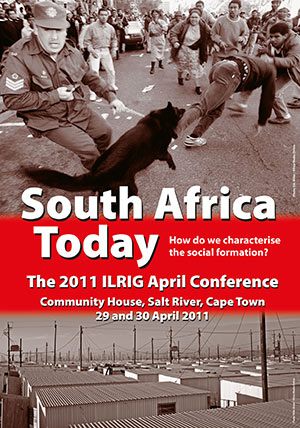

Papers from ILRIG’s 2011 April Conference.

2011 is the 17th year of the achievement of democracy in SA. But in that time, instead of the mass struggles of the 1970s; 1980s and early 1990s leading to radical transformation we have seen a decline in the extent and depth of those struggles and the triumph of a neo-liberal order. South Africa has joined the BRICS as an aspiring power, South African corporations have become global players, the composition of the ruling class is still overwhelmingly white and we are now the most unequal society in the world. At the same time we have an ex-liberation movement in government, carried there by the struggles of a black working class majority and with a ruling Alliance which includes the biggest trade union federation and a long standing Communist Party.

More recently we have seen the rise of movements and community-based activists who have waged struggles quite relentlessly for some 5-10 years – serving as a source of optimism and renewal on the left and yet not galvanising into a social force capable of speaking in its own name, let alone challenging the neo-liberal order. We have also seen a readiness of some organised workers to strike and test the limits of the partnership that comprises the ruling tripartite Alliance.

Part of the many challenges facing activists today is characterising what the nature of the new order is in South Africa today – unlike in the apartheid period where the nature of that order was starkly apparent. This means that activists battle with the tension between the legitimacy of their cause and the legitimacy of the liberation credentials of the current government and its associated democratic institutions in the state.

On the left, in the broadest sense, this tension has been variously characterised as “a society carrying out transformation against residual apartheid forces”; a victim of global forces imposing neo-liberalism “from the North”; a developmental state; a natural consequence of a nationalist or a social democratic project triumphing over a more radical alternative; and even the triumph of neo-apartheid.

How do we characterise this social formation? What configuration of social forces led to this conjuncture and what are the strategic, programmatic and organisational consequences of taking one characterisation over another? How does one’s choice/s inform how one sees international solidarity in Africa and the wider world today?

South Africa Today