by Shawn Hattingh and Mandy Moussouris

The late Stephen Hawkins had the following to say about the onset of the so-called 4th Industrial revolution: “If machines produce everything we need, the outcome will depend on how things are distributed. Everyone can enjoy a life of luxurious leisure if the machine-produced wealth is shared, or most people can end up miserably poor if the machine-owners successfully lobby against wealth redistribution. So far, the trend seems to be toward the second option, with technology driving ever-increasing inequality.”

What Hawkins was highlighting in this statement is that in a different society, machines could be of benefit to all of humanity. However, in the current class based capitalist society, machines pose a dire threat to the majority of people and the onset of the 4th Industrial Revolution will lead to the vast inequalities that already exist increasing exponentially.

World Bank statistics show that currently automation is responsible for 17% of production and services, in 15 years this is projected to rise to 40%. A common held belief by most of the middle class is that automation is a threat only to blue collar workers but this is becoming more and more untrue. The full computerisation of bank tellers, clerks, bookkeepers and pharmacists jobs is an increasing reality and will soon start affecting the work of teachers, doctors, pilots and architects. To understand why mechanisation and automation is being rolled out today; and why this poses such a threat, it is important to understand how they have been used under capitalism in the past and for what purposes.

An important feature of the introduction of machines historically is that a small elite have own them and the value produced by them has been used to increase profits and enrich the few. Whilst historically, machines have been introduced to increase the profits of owners, they have also been used for more insidious reasons.

The initial mechanisation of production occurred in Britain in the late 18th and early 19th centuries. At the time, Britain was a hotbed of class struggle. The ruling class were using their control over the state to dispossess the majority of the population of the right to common lands and force people into factories. This involved the violent expropriation of common land.

In the factories of Britain, artisans (effectively the middle class of their day) did the majority of work. They, as a result of their skills and knowledge, had a great deal of control over the production process which, in turn, gave them status, bargaining power and relatively high wages. Because the owners of the factories rarely understood the production process, they were dependant on the artisans and were held in check by the power of the artisanal guilds. The artisans often used this power to win concessions from factory owners collectively withdrawing labour if they felt they had been wronged.

The owners of the factories introduced machines to invert these relations and to gain greater control over the workforce. The introduction of machines was designed to reduce the need for skilled labour, and allow production to take place based on simple tasks that anyone could do in conjunction with a machine, including children (who became a substantial part of the labour force). This was done to shatter the power artisanal workers had and to replace them with low paid but more importantly, easily controllable workers who were moving to the cities because of the expropriation of the commons. It was, therefore, about power and class relations.

This was fiercely resisted by the artisans who formed the Luddite movement. The Luddites were not opposed to machines themselves, but rather how capitalists were using the machines to undermine their work and role in society. At times this resistance was highly effective and was only broken when the British state deployed 12 000 troops to violently break the resistance. Numerous Luddites were executed, thousands more were arrested and sent to Australia. Mechanisation and greater control over workers by capitalists was literally introduced and enforced by the barrel of the gun.

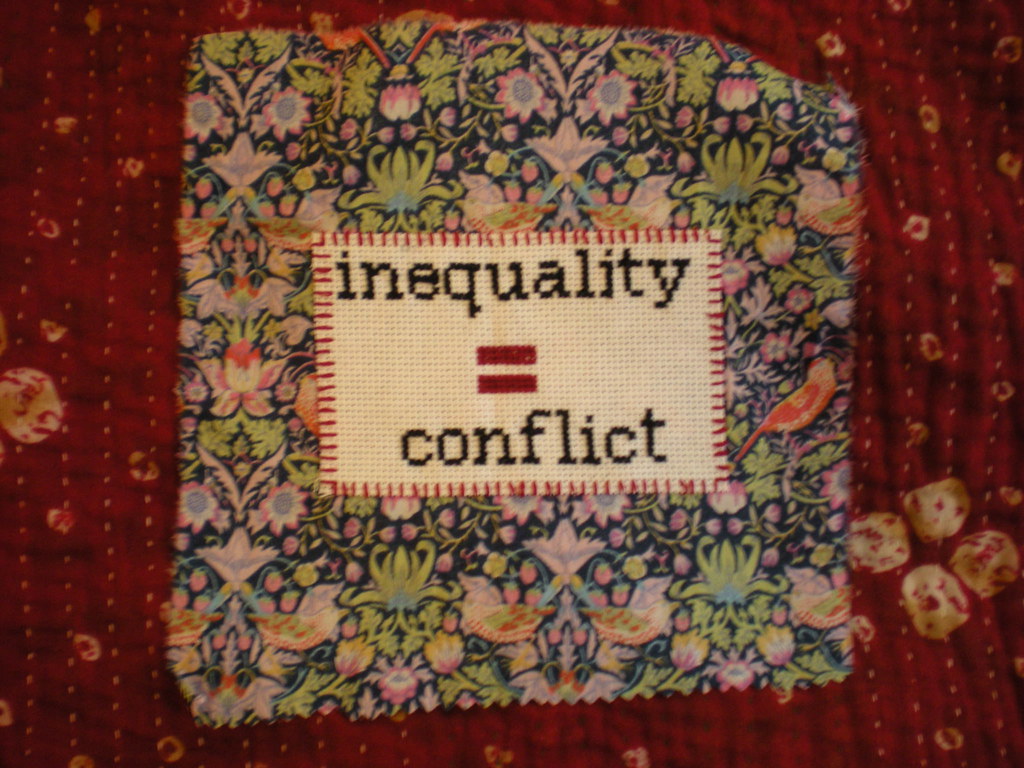

The consequence of this class war through machines, is that inequality grew massively during the first Industrial Revolution. Wages stagnated or declined and only began to rise decades afterwards – not coincidentally when mass worker organising gained momentum again.

The Second Industrial Revolution followed a similar pattern. Mass assembly line production using machines was introduced between 1880 and 1920 to increase profit margins, but importantly it was again to break workers collective power and resistance. During this period, industrial unions had arisen and were at the zenith of their power in industrialised countries.

To shift power back to the ruling class, capitalists introduced Taylorism, which further simplified and sped up work. Workers were placed in stations and using ever more sophisticated machines undertook highly repetitive, simple tasks that required little or no cognitive work. Union members that were vocal or militant could be replaced by anyone off the street, and they were. Workers again resisted – when the Ford Company introduced Taylorism, workers often responded by quitting their jobs on mass. To break this resistance and increase the surveillance of workers Ford hired thugs as ‘security’. Capitalists such as Ford were yet again backed by the state. Again, inequality rose dramatically and wages dropped, again taking years to recover. Child labour also arose many places during the Second Industrial Revolution, and working conditions were dangerous: in the United States between 1880 and 1900, 35 000 workers died in accidents on assembly lines.

Fast forward to the beginning of the 21st Century, what is driving this new wave of mechanisation and automation? As before, there is a fresh bid to increase profits in a global economy that has been stagnating for years and once again, in the centre of 21st Century production – China it is about breaking workers organisation. For the last 15 years, workers in China have been organising to win better working conditions and wages, even in the face of a highly repressive one party state. They have been extremely successful in their struggles. Multinational companies, backed by the Chinese state, have responded to this by a wave of mechanisation and automation. Companies around the globe, to keep up with the competition, have followed suit. The likely outcome will be declining wages and growing unemployment – especially in a context of global stagnation where new jobs are unlikely to be created.

This process of mechanisation, whilst having the potential of producing more and more with less effort and at lower cost, threatens hundreds of millions of jobs. If people do not have work it really does not matter how many things are produced and how much they cost, there will be no one to buy them except the very few elite. This will result in production being aimed more and more at the shrinking few with money and turn the current gap in inequality into a chasm. Unless the way society is structured changes fundamentally. The only way mechanisation can benefit all of humanity is if it is steered towards democratic production for the needs of all of humanity and not the profit of the very few. This will never happen in a capitalist society. It is therefore imperative that we understand that the inherent danger to human kind lies not in the machines but in the system that is using them. That our only hope, under current conditions, is to resist mechanisation until we are able to effect a structural change to society that benefits all.

First Published in Business Day