By Dale T. McKinley

Published in Daily Maverick.

Studies suggest that close to 60% of adults in South Africa are experiencing higher levels of emotional and psychological stress than before the pandemic. This was brought into a much more personal focus when three academic/work colleagues and good activist-intellectual friends/comrades of mine took their own lives.

“At the risk of seeming ridiculous, let me say that the true revolutionary is guided by great feelings of love” – Ché Guevara

Over the past two years the combined and intertwined ravages of an unpredictable coronavirus pandemic and an uncontrollable capitalist system and politics have given rise to a widespread and intensified mental health crisis. A toxic and often deadly cocktail of both objective and subjective impacts has wreaked havoc on human society, and particularly on the mental health landscape.

As the various authors of South Africa’s National Income Dynamics Study (NIDS) – Coronavirus Rapid Mobile Survey (CRAM) Wave 5 report note, these impacts include “fear, anxiety, loneliness, and uncertainty about the future” stemming from both the health-related effects of the virus and the material effects of associated political and economic responses such as “job loss and unemployment, food insecurity, and… hunger”.

This mental health crisis is most definitely global in its reach and character and, not surprisingly, disproportionately affects those who are poor, marginalised and most vulnerable. However, it has been made exponentially worse in those countries where there has long been a generalised public health crisis and more especially where the availability of, and access to, public mental healthcare service is either severely constrained or virtually non-existent.

One of those countries is South Africa. Even before the pandemic hit, a 2018 study by the South African College of Applied Psychology found that one-sixth of the population suffers from anxiety, depression or a substance use disorder, while about 60% could be suffering from post-traumatic stress. Crucially, the study found that only 27% of those with serious mental disorders receive treatment. In the most populous province of Gauteng, the Department of Health recently revealed that the suicide rate had increased by 90% between 2019 and 2021.

Other studies suggest that close to 60% of adults in South Africa are experiencing higher levels of emotional and psychological stress than before the pandemic, with data gathered by Alexander Forbes Health Management Solutions showing that “stress, anxiety, depression, domestic violence, loneliness or isolation and musculoskeletal-related medical conditions are rising among employees”. When it comes to young people/students, the extent of the mental health crisis remains largely hidden because, as Patti Silbert and Tembeka Mzozoyana point out, “in many school communities silence is conflated with coping, with the result that children and adolescents are becoming increasingly disconnected from their personal and collective trauma”.

All of this was brought into a much more personal focus in the latter half of 2021, when three academic/work colleagues and good activist-intellectual friends/comrades of mine – all of whom were in their forties and fifties – took their own lives. In the case of University of Johannesburg (UJ) Professor Pier-Paolo Frassinelli, a letter written by his colleagues to the university management requests an independent “inquiry into mental health conditions at the university” and states that “it is not possible to raise awareness (around issues of) mental health more generally (unless we) speak openly about them and develop strategies to address them”.

Reflecting on the suicides of both Frassinelli and another colleague at UJ, Professor Aziz Choudry, a senior UJ academic makes specific note that within academia, “the impacts of neoliberal restructuring have been extensive and deep, with severe demands placed on academics: money is at the core of everything with careerism being the driving force”. As a result there is “a growing separation of the personal from professional work as well as from larger politics and activism”.

Such realities have become the staple of human experience across a wide array of work and social spaces that encompass formal and government institutions, private businesses and civil society organisations, among others. Indeed, they have become deeply embedded in the very sinews of our individual as well as collective, societal “worlds”.

This includes the “worlds” of progressive political/social justice activism, community and worker organisations, social movements and NGOs; through/in which I have been personally involved for more than 40 years. Contrary to what is often claimed alongside associated and widespread public expectation, in these “worlds” the objective and subjective realities of mental health challenges have far too easily been dismissed, mental health has consistently been pigeonholed into the “private/personal” realm and there has been an abject failure to create enabling and caring spaces for those in need.

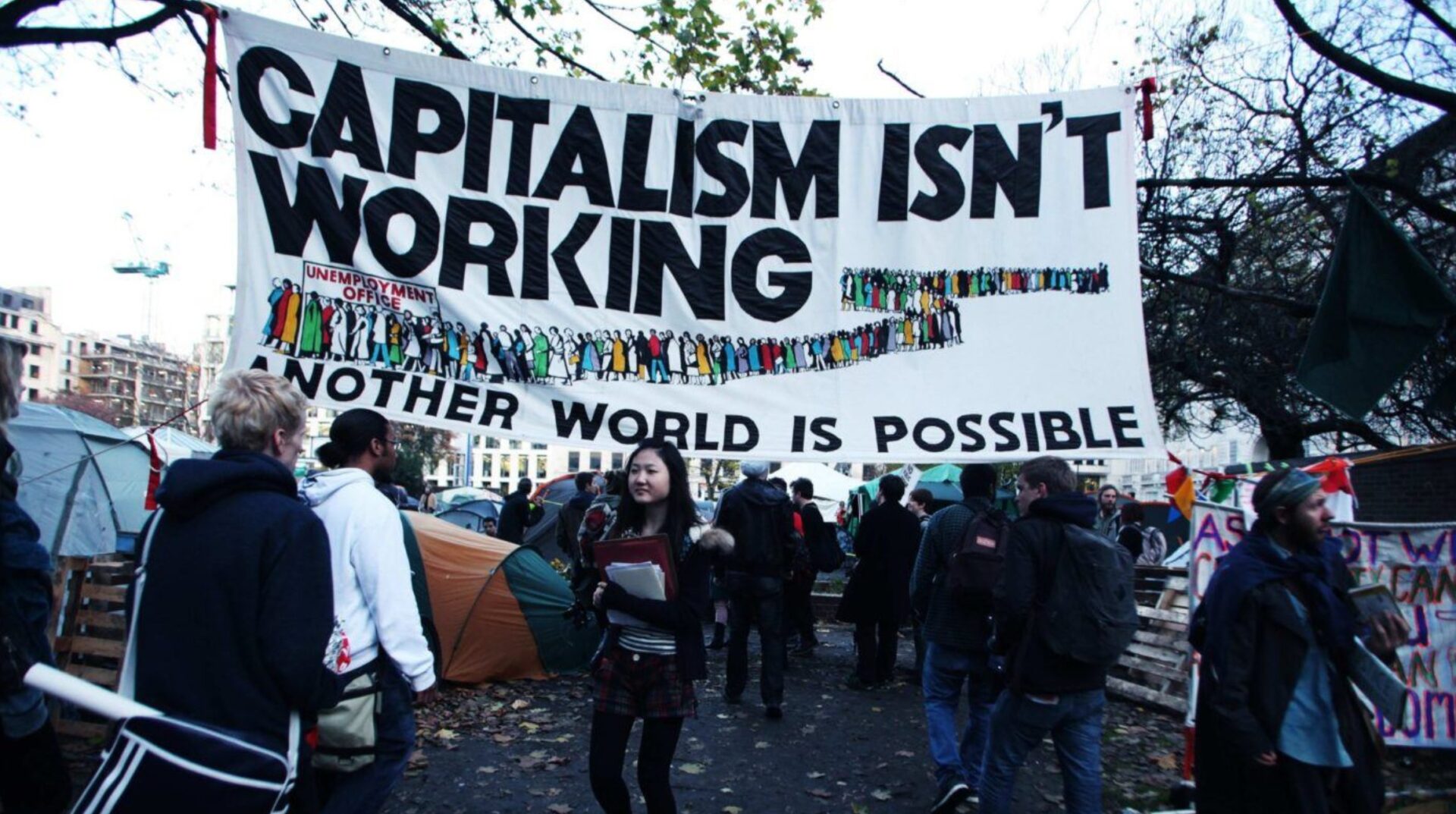

Many would (correctly) note that significant parts of this state of affairs have been with us for quite a long time. However, what must be acknowledged and confronted is that these realities have been taken to an entirely different level by a virus capitalism whose combined character and impact has turbocharged class, racial, gender and religious division and hatred; unprecedented social and economic inequality as well as violence; and, the isolation, individualisation and atomisation of our human lives.

We are faced with a dying capitalist system desperately and ever more destructively trying to do the impossible – save itself from itself, through itself.

Nevertheless, where there is crisis there is always possibility. The deep-cutting, systemically grounded ravages of virus capitalism have given rise to a range of revolutionary possibilities.

Some might see those possibilities through more traditional lenses, for example: as a result of the formation and struggles of both national and global mass movements for change, economic meltdowns or the physical and political overthrow of governments. What I have in mind is much simpler and I would argue, more immediately possible and necessary in the present. Channelling and slightly refashioning Guevara’s statement within our contemporary context, it is that there is nothing more revolutionary than acts of love.

By that I mean acts of an inclusive human love, which re-centre the essential commonality and empathetic nature of our humanness at both individual and collective levels. Such acts encompass but are not reducible to those forms most considered as constituting love – eg, romantic, sexual, familial. Crucially, they encompass everyday acts of individual kindness, respect, caring, empathy and sharing in addition to more general and collective as well as organisational acts of tolerance, inclusivity, solidarity and actions for positive societal change defined by equality and justice.

There are many and varied ways for us to practise such acts of love:

- Recognition and acknowledgement: these are the first steps in holding each other close. Whether related to individual, familial or collective/organisational relationships and settings, we have to first recognise that there is a problem/crisis. Doing so constitutes the foundational act in then acknowledging an endemic and growing reality. This provides the essential opportunity to help roll back associated layers of stigma and denialism and to place mental health at the centre of our varied relationships;

- Space and voice: once the reality has been seen and embraced, this can then allow for spaces – which can be either/both private and open/collective depending on the circumstances – to be created in order to provide an enabling environment to listen, share and/or engage. This is crucial to breaking the silence that in general, envelops mental health issues and in particular has found a comfortable and long-standing “home” within various collectives, institutions and organisations; and

- Support and solidarity: whether “applied” in individual, familial or collective/organisational settings and whether in informal or more formal/professional ways, the availability and accessibility of practical support is essential. Unless otherwise necessitated by extreme exigency or due to an inability to effectively participate and work, such support should be offered without conditionalities. In this way an environment of enveloping solidarity can be forged that feeds feelings of care, belonging and positive ways forward.

At the risk of being attacked and/or caricatured by erstwhile and self-proclaimed “revolutionaries” in the present, it is these acts of love that can constitute not only radically different and effective ways to confront the mental health crisis, but can act as the core antidote to virus capitalism itself.