By Shawn Hattingh

The Public Protector’s report on Nkandla has again unleashed a storm of anger. Radio shows and newspaper columns have been filled with people complaining about the state spending vast sums of money on upgrading the President’s private residence. Rightfully they have pointed out that it is wrong that the state spent R248 million on the project – money which could have been spent on housing, healthcare, and service delivery for the public.

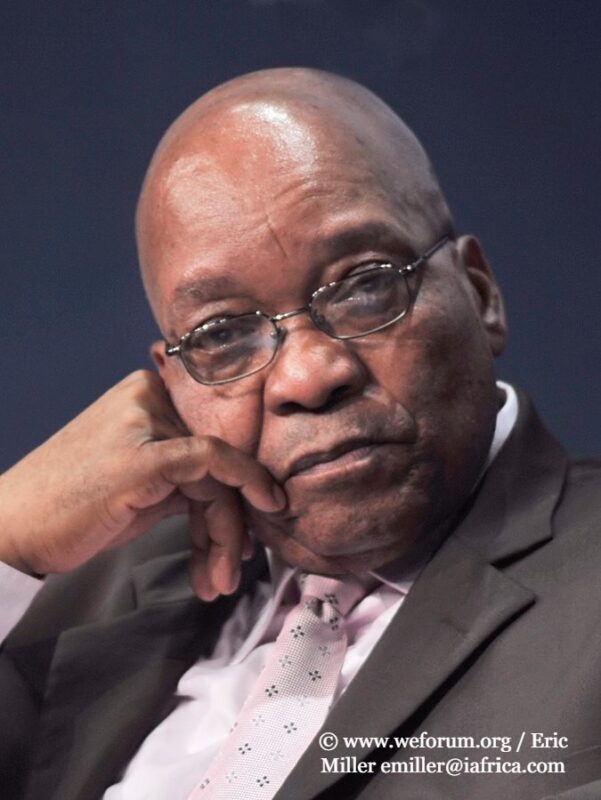

But when it comes to analysing why Nkandla could happen and what it represents, however, most of the analysis has been shallow. In fact, the analysis of why the Nkandla scandal happened and what it symbolises has often taken on racist undertones or has merely been put down to the personal greed of Jacob Zuma. While Zuma has been mired in corruption scandal after corruption scandal, Nkandla points to far larger problems than simply the character of the President or his propensity towards corruption. In fact, it points towards problems associated with capitalism, its neoliberal variant, class rule, and the state.

Getting rich through the state

In society, the state plays a central role in protecting the interests of the ruling class. It is a centralised instrument. Under capitalism this, therefore, has seen states protecting and furthering the interests of capitalists and top state officials who make up the ruling class. As such, state resources are often skewed under capitalism towards disproportionately meeting the needs of the rich. Linked to this, the laws, courts, police and military are the ultimate safe guards of the ruling class’s wealth.

But the state can also be used as a site by an elite to accumulate wealth. In recent history this was evident in countries that were emerging from colonialism. In such countries, local capitalists often did not exist – due to colonialism and the positioning of these countries in the international capitalist order – and for an emerging elite the state offered one of the few paths to accumulate wealth. As such, many “Third World” elites used newly independent states, and their links to capitalists in the “First World”, to amass private wealth; sometimes on a very large scale.

However, even in North America and Europe, being positioned high in the state offered and offers opportunities to amass wealth. Along with the perks that holding high office within the state brings – including large salaries – this has often also taken the form of corruption, including bribery by private capital. For example, in 1961, the West German Minister of Defence was paid a bribe of over R100 million (which given inflation would be over a billion today) in order to ensure the West German state bought fighter jets from Lockheed. Thus class rule, states, capitalism, and accumulating wealth have always gone hand in hand and have often involved outright corruption.

Accumulation through the South African state

By the time apartheid fell, South Africa had developed a local capitalist class. However, due to apartheid, this class was almost exclusively white. Aspiring capitalists that were linked to the ANC, who wanted to own large private companies, were frustrated by these capitalists. In fact, ownership of large corporations remains mostly in the hands of white capitalists.

This has meant that for an aspiring elite around the ANC, like in many other formal colonial countries, the state has offered the most viable way to accumulate wealth. This is why an ANC-linked elite have used the state to open up business opportunities for themselves. The ANC’s and the states relations with capitalists like the Guptas is an example of this. It is also why managers within state-owned companies have been rewarded huge salaries. Linked to using the state to accumulate private wealth, have also been endless scandals. One only needs to think back to the arms deal. Nkandla is a continuation of this and arises because the state is being used as a site of accumulation: Nkandla, therefore, is one outcome of this and a symbol of it.

In fact, Zuma is not alone in using the state to upgrade his own property: recently millions were spent by the state on improving minister’s houses; and tens of millions were spent on the properties of Mbeki and Mandela. But using the state to get rich goes beyond simply improving private houses: the improvement of properties is simply part of the larger drive to make money out of the state and open business opportunities through it. In some ways, this echoes how an Afrikaner elite under apartheid used the state to accumulate wealth and business opportunities in the face of the dominance of white English-speaking capitalists.

Neo-liberalism has made things worse

Under neoliberalism, however, the practice of officials using the state to secure private wealth has become even worse. Privatisation and tendering offer state officials, their family members, and people that are politically connected the opportunity to become extremely rich. Since the adoption of neoliberalism, outright corruption associated with privatisation and tendering across the world has also grown – and like all countries, South Africa has not been immune.

The curse of neo-liberalism in South Africa

Consequently, neo-liberalism in South Africa has amplified the tendency of the elite to use the state to accumulate private wealth and it has ideologically given the ruling class the green light to brazenly loot state coffers. In terms of this, both the ANC-linked elite and white capitalists have been helping themselves.

For an example, one need only think of the state tenders to build the World Cup stadiums. These were awarded to the largest construction companies in South Africa, like Murray and Roberts. It has become clear that such companies colluded with one another to inflate their prices and accumulate wealth fraudulently through this. Nkandla again is another example. The reason too why Nkandla was so expensive was not only Zuma’s desire for a private palace but also because contractors inflated their prices. The architect’s fees alone for Nkandla were R18.6 million. Nkandla, therefore, arises out of and represents how neo-liberalism has intensified state corruption, and how both capitalists and state officials are using the state as a site to accumulate private wealth.

Conclusion

People should, therefore, rightfully be angry about Nkandla. They should fight against this and other forms of corruption. But this fight should not get sidetracked into just the personal flaws of Zuma; because it represents far more than this. In fact, the ruling class using the state as a site of accumulation is a systemic problem that is heightened by neoliberalism. This means to fight corruption we should also be fighting capitalism, the state as an instrument of the ruling class, and perhaps most importantly for the moment the neo-liberal variety of capitalism: because it intensifies using the state to accumulate wealth and encourages blatant corruption.