By Shawn Hattingh and Dale T. McKinley

17 November 2020

First published in Global Labour Column Number 363

Over the past decade, workers – often labour broker or contract workers – have attempted to self-organise outside unions in South Africa in order to take their struggles forward. In doing so they have been collectively trying to address the new reality defined by the precariousness within which they find themselves.

This article traces the history of some of these initiatives with a specific focus on the worker committees that arose in the platinum belt from 2009 to 2013, and more recently the experiments of the Simunye Workers’ Forum (SWF). It examines why the workers, mainly precarious, elected to use these forms rather than unions, and what promise they hold.

Trade unions’ (non)response to restructuring of capitalism

As in many parts of the world, South Africa was severely affected by the capitalist crisis that began in the 1970s. In the decades since, a central responses of South African capitalists to maintain profits has been to restructure the working class by introducing casualised labour on a large scale. Over time, this made it hard for this recomposed working class to build unity and to organise collectively due to greater fragmentation.

Unions in the country have largely been ineffective at organising casualised workers. Part of the reason is that dues from these workers are unreliable and unions feel it does not pay to recruit them. Rather, unions continue to focus on the decreasing number of permanent workers, especially in the state sector, where the largest unions are now to be found. This shows that unions have not fully grasped the reality of the radical changes to the working class As a result, unions are in a general state of decline, both in terms of membership and politically. Their general mimicking of the structure and ethos of ruling class entities such as political parties and the state, where those at the top have power, has meant the changes needed to confront the new reality have not been made.

Worker committees and trade unions in the platinum mines

In 2009 the frustration that workers, in particular precarious workers, had been feeling towards unions began to break out in the country’s platinum mines. That year, a large number of workers in six platinum mines began self-organising and embarked on underground sit-ins and wildcat strikes. These were then followed in 2012 by a wave of wildcat strikes at Impala Platinum, Angloplats, and Lonmin, where the Marikana massacre occurred.

The reasons for this wave of self-organising were often interrelated. Many workers – most of whom were contract, outsourced or labour brokered workers – were unhappy with the multi-year wage agreements that the main union in the sector, the National Union of Mineworkers (NUM), had signed in centralised bargaining and imposed on them. Likewise, on the NUM’s watch, precariousness arose within the platinum sector and affected workers felt the union had been complacent in this. Indeed, the NUM had patently failed on many occasions to defend precarious workers (Sinwell and Mbata, 2016).

The workers involved in this self-organising from 2009 to 2013 used and created new structures – mainly mass meetings and committees – that were based on direct democracy to specifically ensure that any actions and negotiations would be as participatory and accountable as possible. It was this self-organising that gave worker organising in the platinum sector its vitality and militancy during those years, arising amongst workers themselves to address their direct needs and demands. These different ways of organising held within them the potential to revive long term worker militancy.

The seriousness with which the ruling class perceived this ‘threat’, particularly after the 2012 platinum belt wildcat strikes, can be seen in how they – and the state which broadly serves their interests – attempted to violently crush these initiatives. They unleashed the police and military on these workers and surrounding communities, with Marikana being the starkest example. The net result of the state violence, which of course included the infamous Marikana massacre in August 2012, was that by the end of 2013 many workers decided to discontinue self-organising in mass meetings and committees and return to structures sanctioned by the existing labour relations framework – that is, to join a legally registered union.

At the same time, the mining companies largely refused to recognise the worker committees. Their position was workers should be part of a union if they wanted recognition. Through violence and intimidation, the state and mining houses successfully corralled workers back into the framework of state sanctioned labour relations and into a union – now in the form of the Association of Mineworkers and Construction Union (AMCU). While AMCU may not have been the first choice of mining companies, it was viewed as more predictable and preferential to committees and mass meetings. AMCU itself benefitted as, to its credit, it had at least offered some solidarity to the workers at Marikana.

In reality, however, AMCU is not that different to NUM. Like NUM, AMCU’s leadership insisted that the workers’ committees needed be dissolved before joining AMCU, explicitly stating that the committees were a threat to their authority. This was helped along by the lack of a widespread vision at the time amongst workers that structures of direct democracy, like mass meetings and mandated committees, could be a permanent way of organising. Four years after they had surfaced, the workers’ experiments with directly democratic methods of organising on the platinum belt had effectively ended.

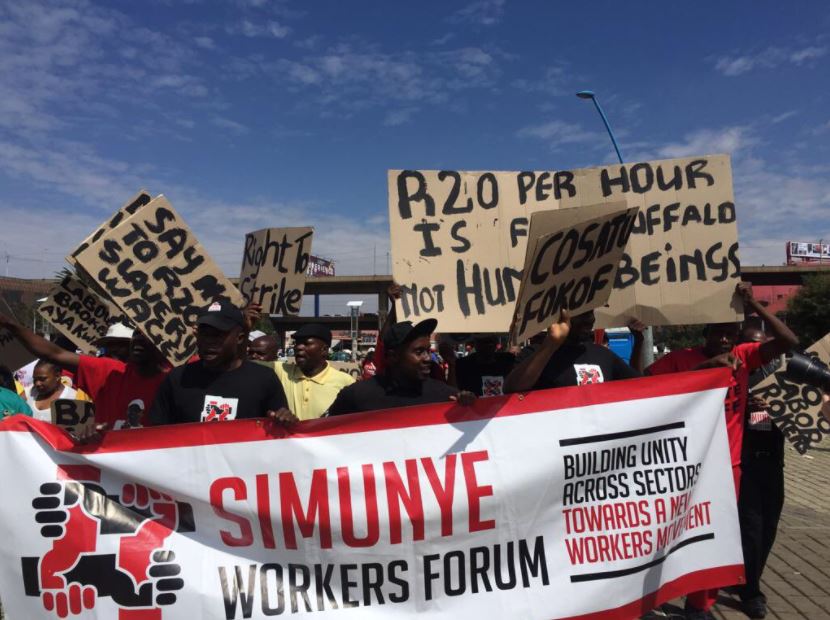

Yet new struggles began to emerge in the industrial heartland east of Johannesburg. These started to be organised outside of unions with the assistance of the Casual Workers’ Advice Office (CWAO) and came together in the Simunye Workers’ Forum (SWF) in 2015. (Simunye means we are one).

The Simunye Workers’ Forum

The CWAO was founded in 2011 ‘as a non-profit, independent organisation to provide advice and support to workers, privileging casual, contract, labour broker and other precarious workers’, according to its website. For the CWAO. the main impetus behind their formation was that ‘the traditional labour movement appears incapable or unwilling to organise the new kinds of workers created by neoliberalism’. For almost a decade now, CWAO’s core focus has been on catalysing self-organisation amongst precarious workers.

After an initial period of outreach, involving identifying and meeting with precarious workers and offering educational and legal advice, a group of workers formed the SWF as a direct expression of self-organisation and a non-union mobilising alternative. Many SWF members had been mobilising for labour brokered and contract workers to win the right to permanent work that had been legislated in the wake of the platinum sector strikes in 2012 and 2013 through an amendment to the Labour Relations Act. Through the activities of the SWF, with the advice and support of CWAO, precarious workers have taken forward struggles and different forms of organising.

Hundreds of workplaces on Johannesburg’s East Rand now participate in the SWF by sending delegates to mass meetings held at CWAO’s office. There are no paid officials or organisers—rather workers organise themselves. At each meeting workers make voluntary contributions of any amount for strike funds and any legal costs that may be incurred (Dor, 2017).

As a result of the collective coming together of workers through the ‘vehicles’ of the CWAO and SWF on the basis of practical workplace needs and struggles, there is an added impetus and desire to go out and get others to join the collective. This allows workers to lead struggles and new forms of organisation that do not revolve around rigidly defined legal, organisational, political or ideological status, identity or affiliation.

For SWF members, the road so far travelled is representative of a simple yet profoundly different approach. It is an approach that is focused on the bulk of contemporary workers – precarious workers – and their struggles in the workplace.

Nonetheless, there are clear challenges. The very nature of precarious work creates permanent instability and significant barriers to be able to organise and mobilise all the workers. This has led to ongoing debates about turning SWF into a union itself. Additionally, workers relate how this fragmentation sets workers against each other, especially when it comes to relations with permanent and unionised workers.

Regardless, the CWAO/SWF are incipient ‘homes’ for bigger battles that seek to forge a national workers’ movement that can engage in larger-scale complementary struggles on a more class-wide basis. In many ways, they continue to carry the ethos of self-organising that surfaced in the wave of struggles in the platinum belt. Indeed, SWF’s experiment with different forms of organising is an attempt, however limited, to recompose working class power in order for casualised workers to find their own collective ways to organise and confront the challenges they face in the neoliberal period.

This column summarises a chapter from Workers Inquiry and Global Class Struggle: Strategies, Tactics, Objectives.

Shawn Hattingh works as a research and education officer at the International Labour Research and Information Group (ILRIG) in Cape Town, focusing on research and education on historical and contemporary examples of workers organising on the basis of direct democracy. He is influenced politically by Democratic Confederalism.

Dale McKinley is an independent writer, researcher and lecturer and research and education officer for ILRIG. He is a veteran political activist who has been involved in social movement, community and liberation organisations and struggles for close to four decades. He has published widely on various aspects of South African, regional and global political, social and economic issues and struggles.

References

Dor, L. (2017) ‘Simunye Workers Forum’, Workers World News, 107(9).

Sinwell and Mbatha (2016) The Spirit of Marikana. The Rise of Insurgent Trade Unionism in South Africa, London: Pluto Press.