By Shawn Hattingh

26 November 2020

First published on Medya News.

The sight of people marching and undertaking protests to occupy land has become common under the COVID-19 lockdown in South Africa.

In fact, since the beginning of COVID-19, a new wave of struggles for housing has taken place in the most populous provinces in South Africa: Gauteng and the Western Cape. This has seen tens of thousands of people mobilising to occupy land and erect shelters in order to try and solve by themselves the housing crisis that exists for the majority of South Africans.

Even before COVID-19, South Africa faced a massive housing shortage. Officially, according to the Minister of Human Settlements, there is a housing backlog of 2.1 million units in the country. In Gauteng alone, the state estimates the housing backlog to be in the region of 800,000 units; while in the Western Cape, the figure stands at 575,000. The reality is that even this is an understatement.

Millions of people not only live in informal settlements, but also in shacks that they have to rent from landlords in the backyards of formal houses – something which the official statistics tend to gloss over. Even people that have received housing from the state often face a situation whereby the houses are shoddily built and in some cases even structurally unsound. The right to housing, therefore, has not been realised in South Africa for millions of people and this has been at the heart of the struggle for housing that we have seen in the country under the COVID-19 lockdown.

The legacy of apartheid was made worse by neoliberalism

The housing shortage, which mainly impacts on the black working class, is nothing new to South Africa. Under apartheid, the state attempted to forcefully keep the majority of the black working class in rural areas as a pool of cheap migrant labour for mines and farms. The state also attempted to spend as little as possible on urban housing for the black working class: thus, a housing shortage of 2 million units already existed in 1994.

Yet, the state under the African National Congress (ANC) too has failed to address the housing shortage. This has to do with the deal that was done by the ANC leadership and a small section of white capitalists leading up to the 1994 elections, along with the implementation of neoliberalism. In the lead up to South Africa’s 1994 elections, the ANC entered into negotiations with the apartheid state and the ruling class. A deal was eventually made that would see white capitalists (a small section of the white population that own the means of production) being allowed to keep their businesses and wealth. In return, the top leaders of the ANC were allowed to take over the state and some were also given shares in big companies.

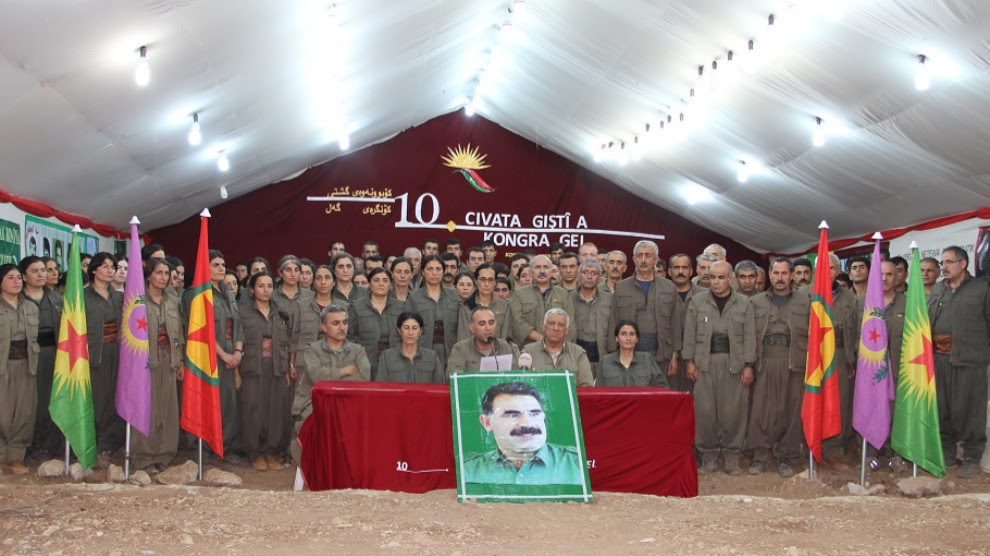

Through this, many of the leaders of the ANC became part of the ruling class in South Africa after 1994. As has been pointed out by Abdullah Ocalan, the nation state cannot bring true freedom and this has been seen in South Africa. This deal, too, meant that the actual structure of the state was not changed and capitalism was kept in place. With this, the hopes that millions of people in South Africa had of a more equal, non-racial and non-sexist society were severely undermined. It also severely undermined addressing the massive housing shortage that existed and which still exists in South Africa.

The ANC once in power also pushed through neoliberalism, which further increased the problems around a shortage of housing for the black working class. This implementation of neoliberalism favoured big businesses, but it also helped sections of the ANC get rich through tenders from the state and outsourcing. Indeed, many people linked to the ANC through neoliberal policies have received tenders to build housing projects for the working class, but to make increased profits, costs have often been cut – leading to poor quality housing. In fact, through the state, the leaders of the ANC became part of the ruling class – along with white capitalists – and neoliberalism advanced their common class interests to the detriment of the black working class – and this can be seen in the shortage of housing that still exists in the country.

Capitalism in South Africa has always been based on the very low wages of black workers. After 1994, this did not change. This is why the legacy of apartheid capitalism still exists and millions of black working class people remain economically exploited, racially oppressed and experience housing shortages or live in poor quality housing. ‘1994’ did not bring liberation for the working class as a whole. In particular, however, the black working class has remained the most exploited and oppressed.

COVID-19 has made the housing shortage worse

Under COVID-19, the economy has seen a dramatic decline and the ruling class has tried to maintain profits through mass retrenchments. Over 42% of people are now unemployed in South Africa. Before COVID-19, many people were renting shacks in the backyards of landlords. Despite the state having a moratorium on evictions during the COVID-19 pandemic, these landlords have been illegally evicting hundreds of thousands of people, who now due to the repercussions caused by COVID-19, don’t have an income.

These mass evictions, along with neoliberalism and the legacy of apartheid, has fuelled the land occupations and housing struggles in Gauteng and the Western Cape that we have seen over the last few months. Through these struggles, tens of thousands of people have won some land to erect shelters on. Nonetheless, the state has attacked these occupations through the police and the struggle continues.

The reality though is that unless a new movement arises out these housing struggles that addresses and seeks to overcome the nation state and capitalism, a housing crisis will always exist for the black working class in South Africa as the structures of the state and capitalism are designed to exploit the black working class as cheap labour in the country. The task is to build the current housing and land struggles into a force that can truly transform South Africa and address the continued legacy of apartheid. In that, the path to freedom lies and it is only through such struggles that the need that people have for housing can be truly addressed.

Shawn Hattingh is a member of the International Labour Research and Information Group (ILRIG).